This article is part of the themed collection: 2025 Pioneering Investigators

https://pubs.rsc.org/en/journals/articlecollectionlanding?sercode=cc&themeid=17ad222a-4147-4a99-9a55-fe3e92abbc2f

Engineered extracellular vesicles: an emerging nanomedicine therapeutic platform

Jingshi Tang†a, b, Dezhong Li†a, b, Rui Wang a, b, Shiwei Li a, b, Yanlong Xing* a, b, Fabiao Yu* a, b

a. Key Laboratory of Emergency and Trauma, Ministry of Education, Key Laboratory of Hainan Trauma and Disaster Rescue, Key Laboratory of Haikou Trauma, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hainan Medical University, Hainan Medical University, Haikou 571199, China b. Engineering Research Center for Hainan Bio-Smart Materials and Bio-Medical Devices, Key Laboratory of Hainan Functional Materials and Molecular Imaging, College of Pharmacy, College of Emergency and Trauma, Hainan Medical University, Haikou 571199, China. c. † These authors contributed equally.

Chem. Commun., 2025,61, 4123-4146 |

- DOI

- https://doi.org/10.1039/D4CC06501H

The intercellular communication role of extracellular vesicles has been widely proved in various organisms. Compelling evidence has illustrated the involvement of these vesicles in both physiological and pathological processes. Various studies indicate that extracellular vesicles surpassed conventional synthetic drug carriers, owing to their abundance in organisms, enhanced targeting ability and low immunogenicity. Therefore, extracellular vesicles have been deemed as potential drug carriers for treatment of various diseases and the related studies increased rapidly. Here, we intend to provide a comprehensive and in-depth summary of recent advances in the sources, delivery function, extraction and cargo-loading technologies of extracellular vesicles, as well as the clinical potential in constructing emerging nanomedicine therapeutic platform. In particular, the microfluidic-based isolation and drug-loading technologies, and the treatment of various diseases are highlighted. We also make comparison between extracellular vesicles and other conventional drug carriers and discuss the challenges in developing drug delivery platforms for clinical translation.

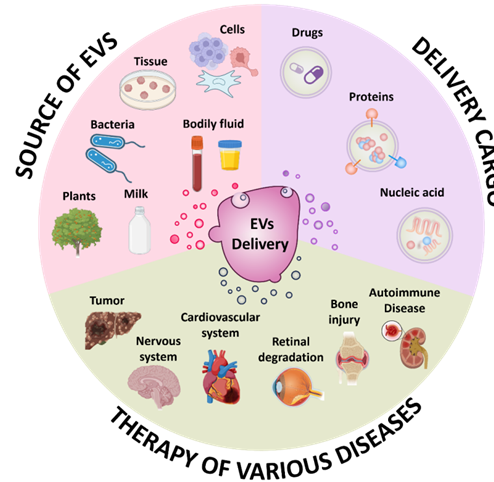

Scheme 1. The schematic illustration of the sources of EVs, the types of drugs loaded and the treatment of diseases using EVs as drug vehicle.

Introduction

In the field of targeted drug delivery, the research advances on nanosized drug carriers have promoted the development of modern therapeutic system. Typically, nanocarriers with a lipid-enclosed structure have been the most interesting focus in the past decades, among which synthetic nanocarriers and extracellular vesicles (EVs) represent the two main types of nanostructured systems.1 It has been reported that in clinical drug delivery, synthetic nanoparticles are easy to be quickly cleared by the immune system mediated by macrophages, resulting in poor stability in circulation and difficult to effectively deliver to specific sites. In contrast, EVs can effectively escape the phagocytosis and clearance of the body's immune system, without triggering a strong immune response, so that it has a longer cycle time and higher delivery efficiency in the body.1 EVs are nanoscale membrane vesicles with phospholipid bilayer structure that are actively released by living cells.2 According to their distinct biogenesis pathways, EVs could be categorized into three types: exosomes (30-200 nm), microvesicles (100-1000 nm) and apoptotic bodies (500-2000 nm).3 A good many reports have provided evidence on the vital function of EVs in intercellular communication, since EVs transport various cargos (proteins, lipids and nucleic acids) that are inherited from their mother cells to other living cells locally and at distance sites.4 Therefore, EVs have been regarded as critical biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis.5 On the other hand, the lipid layer structure of EVs can enable the loading of external payloads (e.g. therapeutic drugs) into the vesicles, which preserved their natural compatibility in organisms. Thus, the idea of using EVs as drug carriers to achieve the precise delivery of cargos (protein, lipid, nucleic acid and drugs) and improved treatment of diseases has been continuously studied.6 Additionally, EVs have intrinsic tissue homing properties, which makes it attractive to explore their potential in developing modern drug delivery nano-systems. EVs are widely present in bodily fluids and can be obtained via various sources including living cells, tissues, bacteria, dietary and plants. Compared to the conventional engineered nanocarriers, EVs have been extensively investigated to be drug delivery nanocarrier owing to the above merits and are expected to be widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of various types of diseases (Scheme 1). Here, we systematically summarize the sources, structures, biological functions, extraction methods, characterization, and preservation of EVs. The drug delivery methods and types of EVs as well as their progress in disease treatment at the current stage are summarized in detail. Finally, the challenges and future perspectives in harnessing EVs as modern nanomedicine treatment platform are discussed.

2. Biogenesis, source and function of EVs

2.1 Biogenesis

Based on their different origin of biogenesis, EVs of different sources have different biological functions and structural compositions, and therefore, affecting their application prospects in drug delivery.7 Exosomes are the smallest extracellular vesicles. The formation of exosomes requires the cell membrane bud inward to form the early endosome. With continuous evolution, the early endosome transforms into the late endosome then the late endosome membrane budding inward into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) with multiple intracavitary vesicles (ILVs). The MVBs can undergo fusion with lysosomes, leading to the degradation of ILVs.Additionally, it can fuse with the plasma membrane of the cell and release ILVs through exocytosis, ultimately giving rise to exosome. MVs are formed by outward budding and fusion of the plasma membrane of the cell. Apoptotic bodies are produced by cell apoptosis. The presence of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic bodies acts as an "eating me" signal to promote their recognition and clearance by phagocytes such as macrophages.8 In this review, mainly the applications of EVs (exosomes and microvesicles) were discussed and exemplified.

2.2 EVs from various sources and their function

2.2.1 Living cells

In theory, almost all cell types can secrete EVs, and EVs from different sources usually retain the characteristics of the parent cell. Different types of living cells including tumor cells, MSCs, immune cells etc could generate EVs. Isolation of EVs from cell culture media is currently privileged. EVs derived from different living cells preserve their own biological functions, which could be employed to develop a variety of new biomedical nanotherapeutic platforms. Since EVs inherited the contents and properties of parental cells, they also exhibited homing effects to the original tissues or organ,9 which exerted targeted therapy to the diseased niche of origin. Typically, tumor derived EVs played vital role in communication between tumor cells and other living cells in the adjacent or distant environment, and therefore could be applied to diagnosis and treatment after loading cargos for therapy.10 For instance, glioma-derived EVs could be encapsulated with non-coding RNA and had the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which acted as a non-invasive diagnostic marker to monitor tumor progression and treatment response.11

MSCs widely existed in highly regenerative human body parts, such as bone marrow, embryo, human umbilical cord etc, which had the therapy effects for various diseases. Moreover, MSCs derived EVs have been noticed to play important role in disease treatment as cell-free therapy tools, attributing to their own function and low risk of immune rejection. For instance, EVs produced by the continuously proliferating human MSC 544 cell line, was utilized to carry paclitaxel (PTX) and doxorubicin (DOX) and applied to different cancer cell cultures and showed significant anticancer effects.12 Exosomes derived from bone marrow MSCs contain a variety of proteins, nucleic acids, and DNA, which was successfully utilized as drug delivery carriers for the treatment of liver diseases through immune regulation, inhibition of cell apoptosis, and promotion of tissue regeneration.13 Embryonic stem cells are pluripotent stem cells with the ability of unlimited proliferation. Zhu and colleagues prepared c(RGDyK) -modified and PTX -loaded ESC-exosomes, which showed better targeting ability and treatment of glioblastoma (GBM).14

Immune cells include macrophages, dendritic cells and natural killer cells (NK). EVs derived from immune cells can mediate crosstalk between innate and adaptive immunity and play an important role in regulating the progression and metastasis of cancer. It also has important potential in cancer diagnosis and immunotherapy, as well as chemotherapeutic drug delivery.15 Macrophages are widely distributed in the body and can be polarized into M1 and M2 macrophages with different functions. M1 macrophages inhibit tumor growth by releasing proinflammatory factors, while M2 macrophages tend to promote tumor growth and immunosuppression. Zhao and colleagues loaded the chemotherapy drug docetaxel (DTX) into M1 macrophages-derived exosomes and established a DTX-M1-Exo delivery system, which could induce the transformation of naive M0 macrophages into M1 phenotype and achieve long-term M1 activation.16 Umbilical cord blood (UCB) -derived M1 macrophage exosomes (M1 Exos) loaded with cisplatin could target the tumor site of ovarian cancer and reverse cisplatin resistance.17 On the other aspect, M2 EVs had a great application prospect in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Platelet membrane-modified M2EV was constructed by membrane fusion technology to simulate the interaction between platelets and macrophages and displayed a strong targeting ability to atherosclerotic plaques.18 Dendritic cell (DC) derived small EVs (DsEVs) could induced potent antigen-specific immune responses in vitro and in vivo and enhanced antitumor efficacy after adding with ovalbumin.19

2.2.2 Bodily fluids and tissue

EVs are widely present in various body fluids of humans, such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, ascites etc. Blood EVs based biomarkers provide a semi-invasive opportunity for "liquid biopsy".20 Both plasma and serum are the sources of blood EVs, but there are significant differences. EVs in serum contain more platelet-derived EVs. Meanwhile, the particle content and proteomics contained in EVs in serum are also different from those of plasma-derived EVs.21 Blood-derived EVs have natural brain-targeting ability, which can be used for drug delivery to cross the BBB. It has been reported that dopamine was loaded in blood-derived exosomes, which could be used for targeted treatment central nervous system diseases.22 Urinary EVs (uEVs) can reflect the physiological and pathological changes of the kidney, urinary system and prostate tissue. Proteins and miRNAs contained in uEVs can be used as biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of diabetic nephropathy.23,24

Tumor tissue derived EVs could be engineered by conjugating with LC3 and loading with active cathepsin B (CTSB), which could act as anti-angiogenic targets in bladder cancer.25 Adipose tissue-derived EVs (Ti-EVs) could be utilized as metabolic signaling molecules, therefore, was applied to study the lipid-related metabolism.26

2.2.3 Bacteria

EVs derived from pathogenic organisms could effectively modulate human pathophysiology and served as vehicles for drug delivery. It was reported that probiotics derived EVs can achieve therapeutic effects by regulating macrophage phenotype. For instance, Lactobacillus plantarum-derived EVs could alleviate inflammatory skin diseases by inhibiting the expression of HLA-DRa, a surface marker of M1 macrophages, and triggering the polarization of M2 macrophages with anti-inflammatory effects.27 EVs secreted from Lactobacillus johnsonii could activate M2-type macrophages and inhibit NLRP3 activation in intestinal epithelial cells by turning off ERK signaling pathway to fight diarrhea diseases.28 Increasing number of studies had found that bacterial EVs (BEVs) affected host immune response and bacterial pathogenicity, participating in the occurrence and progression of cancer through immune regulation. By surface decoration of tumor antigens or immunostimulatory DNA sequences, vaccines and immunotherapeutic agents were prepared to produce anti-tumor effects.29,30,31 BEVs, especially those from Gram-negative bacteria, had the advantages of providing a variety of antigens and adjuvant molecules and being safer than traditional live attenuated vaccines.32 Studies have shown that BEVs were involved in human systemic diseases. For instance, BEVs derived from gut and pathogenic bacteria were recognized by the host, which could trigger inflammatory response or mediate immune regulation, thereby interacting with the hos.33

2.2.4 Dietary source

Recent years, dietary derived EVs have come into researchers’ vision since they have the advantage of easy availability. Milk is a nutritious and safe food source, which can be produced in large scale. Milk-derived EVs (mEVs) isolated by UC and loaded with glycyrrhetinic acid by co-incubation could be used for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Based on the transwell artificial mucus model, it was found that mEVs could overcome airway mucus and promote lung targeting. When compared with the Chinese medicine simplex component GA at the same concentration, mEVs@GA had a stronger anti-inflammatory activity. Researchers proved that inhaled administration of mEVs@GA reduced the levels of inflammatory factors.34

2.2.5 Plants

EVs can also be obtained from different plants including cucumber, ginger, lemon, broccoli and Chinese herb ginseng. Recent years, plant-derived EVs (PDEVs) have attracted researchers’ attention, owing to their low cytotoxicity, low immunogenicity and easy accessibility.35 PDEVs can encapsulate both hydrophilic and hydrophobic drugs, stabilize in the GI tract, and serve as nanocarrior platforms for oral medications.36 Scientists had successfully isolated EVs from tree sap and cucumber juice, which were both successfully utilized for drug loading.37,38 Ginger derived EVs contain gingerol, which enhances the targeting ability, biocompatibility, and absorption characteristics of drugs in the small intestine as a drug carrier.39 Lemon derived EVs (LDEVs) isolated from lemon juice arrested gastric cancer cells in S phase and induced apoptosis, by producing reactive oxygen species.40 The LDEVs were modified with heparin-cRGD and loaded with DOX, which dissipated intracellular energy through endocytosis, reduces ATP production, and effectively overcomes the multidrug resistance of ovarian cancer.41 On the other hand, PDEVs derived from plants such as broccoli, pomegranate, apple and orange have been found to transport therapeutic miRNAs and reduce miRNA degradation in the presence of RNase. In addition, PDEVs have been discovered to transport trace amounts of phytochemicals such as flavonoids, anthocyanins and phenolic acids, which exhibited therapeutic potentia.42,43 Surprisingly, ginseng derived exosomes-like nanoparticles could penetrate the BBB and target the treatment of glioma by promoting the activation of M1 macrophages and regulating tumor microenvironment.44

Summary and future perspectives

In summary, EVs show great potential in disease treatment due to their unique biological characteristics and are becoming a promising new drug carrier. They can enable targeted drug delivery, improve the effectiveness of drug therapy, and reduce side effects. In recent years, as the research in the field of EVs drug delivery continues to deepen, there are a few EVs-related clinical studies in the planning or trial stage. Although exhibiting its good safety characteristics, the current effective use of EVs in clinical treatment has not been realized. Before the transition from the laboratory to clinical application, there are still a series of challenges to overcome.

First, the yield of EVs in cell culture is low, scalability and high purity preparations are required, which increases the difficulty of large-scale production, and how to efficiently produce enough EVs and solve the problem of low yield is crucial. It has been reported that the yield can be increased by genetically engineering cells, changing cell culture conditions, 3D culture, and optimizing the separation and purification methods of electric vehicles. 226

Second, due to the heterogeneity of EVs, there are uncontrollable differences between batches of EVs isolated from different sources, raising reproducibility and quality control concerns. Therefore, each step involved in EV isolation including the selection of EVs sources, separation methods, characterization methods, storage conditions and the loading of therapeutic drugs, should be standardized to ensure the quality and efficacy of EVs.

Third, another significant challenge in clinical translation is the potential immunogenicity of EVs. EVs from non-autologous sources may trigger an immune response from the receptor, leading to adverse reactions. To reduce the risk of an immune response, one possible strategy is to use EVs from the patient, or to engineer EVs to express immunosuppressive factors or "humanize" their surface markers. At the same time, it is important to accurately assess the potential immunogenicity of EVs to avoid adverse events in patients. In addition, overcoming the problem of selecting cell lines and animal models is also an important issue that deserves attention. This makes it necessary to establish standard operating procedures. 129

Fourth, when conducting clinical trials, regulatory approvals are normally regarded as one of the most challenging aspects. To meet regulatory requirements for clinical trials and commercialization, researchers, regulators and industry stakeholders need to evaluate the safety and efficacy aspects of EVs.

Accompanied by the rapidly growing knowledge on EV-related research, advanced technologies start to exert their influence in this field, for instance, synthetic biology and artificial intelligence (AI)-driven EV analysis. The introduction of synthetic biology has brought new possibilities for the clinical transformation of EVs. Using bionic EVs to mimic the properties of natural EVs with great repeatability, researchers have designed engineered EVs with precise cargo composition, size, and surface characteristics to meet the needs of a variety of therapeutic and diagnostic applications.227 In addition, bionic synthesis makes it possible to produce EVs with better stability and higher cargo carrying capacity, which can be customized according to the specific needs of each patient, opening a broad development space for personalized medicine. AI can analyze large amounts of complex EVs data to identify unique patterns and characteristics associated with specific diseases. The researchers combined spectroscopy techniques with AI, which significantly improved the data processing capability and diagnostic accuracy of EVs analysis.228 In the future, AI will be involved in various aspects of EV research, which would largely enhance the efficiency of analysis and disease diagnosis.

In general, although there are current technical challenges, with the rapid development of pharmacology, materials science and nanoscience, we believe that these issues will be solved in the future, and the application of EVs as a modern drug carrier will be promising, possibly even for clinical translation.